Raiders & Traders

Born of a hostile northern environment, strong, fatalistic, individualistic, searching

for riches and expecting little more than to die sword in hand, it's hardly surprising

the Vikings were the terror of their age. The first raids in the late 790's had

huge impact because of their unsuspected ferocity. The trickle turned to a flood,

as word spread through Scandinavia of the wealth to be had. What were once isolated

raids became organized plunder, single ships growing to dozens, eventually to

number in the hundreds. With massive shows of force, extortion became just as

effective as actual battle. And as might be expected, the price rose year by year.

Starting in 840 in Ireland and 850 in England, the armies did not return home,

but built fortifications and stayed over until spring. In Ireland, it would be

the Vikings who would found the first real towns, trading centres such as Dublin,

Cork and Limerick. By 870 the Vikings seized York and took control of a huge area

of central England. This area eventually had such a large Norse population that

it came to be called the Danelaw, because Danish Law took precedence over the

local customs. Although the tide of control would flow back and forth between

the local kings and the foreign invaders, it would not be until about 1010 in

Ireland and 1040 in England that the Viking kings would be expelled. Some historians

consider that the Vikings would rule all in the end, considering the Conquest

of England by William of Normandy in 1066 to be the last great Viking invasion.

"Always keep weapon close to hand.."

Says the Havamal, a collection of folk wisdom from the Viking Age. Although the

Vikings who eventually formed the standing armies were for the most part professional

warriors, this was certainly not true of the earliest raids. The world of the

Norse was a violent one. A man was expected to guaranty his own security, with

sword, spear or axe if need be. This created a culture where the basic skills

of armed combat with the tools at hand were considered a normal part of a child's

education. Although women rarely took part in battles, they too might be required

to defend home and children. A wise father would see to it that his daughters

could at least defend themselves.

The primary weapon was the double edged broadsword. By the beginning of the Viking

Age, the sword had assumed the basic shape that it would retain up through the Middle

Ages. The blade was wide and long, straight sided with a simple point. It ranged

from about 80 to 100 cm long, fitted with a simple bar cross guard and large pommel for

balance. Typically a sword weighs only a kilogram or a bit more - the blade's strength

comes from the width of the blade, not by its thickness. The finest quality swords

were given names, passed down through generations, and might have a reputation greater

than the man who held it.

The Danes, especially, were responsible for reintroducing the axe back into combat,

a weapon neglected since before the Romans. With a two kilogram head behind an 15

to 20 cm blade set on a one meter haft, the specially designed 'battle axe' was a

true terror weapon. Swung with two hands, such a blade would shatter shields and literally

could cut a man from 'crown to navel'. As well as fighting axes, the Vikings were

especially fond of light throwing axes - which would do damage even if the back side

struck a foe. For most however, the same axe that chopped daily fire wood was pressed into

fighting use. Typically, these would be a similar weight to a modern felling axe,

perhaps a kilogram and a half on a handle suitable for one or two hand use.

The third main weapon of the Viking was the spear. In its common form, it was designed

primarily as a thrown weapon for hunting. Set on top of a 1.5 to 1.8 metre long shaft

of ash, the slender but thick blade was secured by means of a sturdy conical socket.

The specialized hunting spears designed for hunting aggressive game such as boars

or bears were also turned to killing the most aggressive opponents of all. These

had longer, leaf shaped blades, with narrow 'wings' running off from the base of

the blade.

Long range combat was carried out with arrows. The 'cloth yard' shaft, as long as

a mans arm, was propelled with wooden bows with an oval cross section. Each shaft

was tipped with a forged iron head . This could be either a leaf shaped 'broad head'

originally intended for hunting, or a special tapered pyramid point designed to pierce shields

and armour. For extreme close quarters, a heavy knife with simple slab wood or antler

handle was worn at the belt. The Norse favored a distinctive shape with a straight

bottom edge and diagonal line to the point called a 'seax'. (It was from this knife

that another group, the 'Saxons', got their name.) Size of the seax could vary from

small tools with 10 cm of blade to almost sword length versions.

To protect themselves, each Viking would carry a large circular wooden shield.

About one metre in diameter, it was formed of a set of thin planks bound together

by an iron rim. It would be reinforced at the back with several metal strips.

One of these ran along the mid line, going across a hole in the center plank to

form the handle. The gap was covered on the front side with a dished bowl of metal

called a 'shield boss'. Altogether, such a shield would weigh about 4 kg. Standing

side by side with just enough room between them to swing their swords, the Vikings

would from a 'shield wall', their basic defensive formation.

Those with the wealth to afford it would wear a chain mail shirt. Mail is composed

of thousands of individual rings, each interlocked to those around it. The result

is a flexible 'cloth' of metal which provides good protection against cuts. Mail

is very heavy however, a shirt with long sleeves and extending down to mid thigh

would easily weigh 15 kg or more. Even worn over a thick padded vest, or gambeson,

mail provides poor protection against impact - and arrows easily penetrate it.

A clue to its desirability, despite these flaws, can be seen on how Saga tales

describe the boasts of chieftains. 'My wealth is such that I can equip all my

household guard with mail shirts.' Obviously this was as much a statement of status

and economics as much as it was physical power. The average warrior was more likely

to wear a vest of thick leather, perhaps reinforced with iron rings or bars. Perhaps

not as high status, this more practical armour was almost as good against cuts,

and certainly protected the ribs better against impact.

The most fragile part of the body is the head, and every warrior would try to

get some kind of helmet to cover themselves. Most were formed of three strips

of metal, two forming the crown and the third going around the temple. The gaps

between might be filled with dished out iron plates, or with thick leather stiffened

by boiling in wax. The front strip often extended down over the brim to form a

simple nasal to offer some protection to the front of the face. More elaborate

helmets might have metal plates hanging down to cover the sides of the head or

face, or even a curtain of flexible chain mail. In every case however, what is

most important is what was NOT attached - and that is horns! There is not one

single helmet from the Viking Age that has ever been discovered with horns. As

common as this popular image of the Viking warrior with the horned helmet is -

there is not a single piece of historic evidence for it. The romantic image of

the windswept Hero in the horned helmet is purely the product of the Victorian

imagination.

Goods from the Known World:

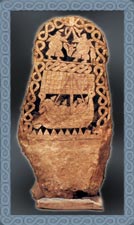

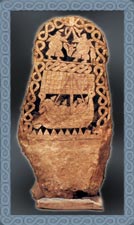

By the 900's, raiders had been largely replaced by traders. Norse merchant adventurers

would adapt the longship hull to create the sturdy freight hauling vessel called

a knar. Wider and deeper, the knar still shared the flexibility and shallow draft

of the warships. The sample found at Roskilde in Denmark is thought to be typical, about

15 m in length, with a cargo capacity of around 30 cubic metres. These were primarily

sailing ships, with an open hold in the centre and only a short length of deck at

bow and stern. In them, they were able travel the length and breadth of the world known

to the Europeans - and beyond. There were regular voyages between Norse established

trade centres such as Dublin, Viking captured towns such as York, and the major centres of

Europe such as Paris.

By taking the knar hull and scaling it down by about a third, it was possible

to produce a vessel still large enough to hold considerable cargo, but now small

enough to make overland portages possible. It was in boats like this that the

Norse merchants, mainly Swedes, would travel the eastern river systems from the

Baltic down to the Black Sea, Constantinople and the riches of the Middle East

and beyond. Goods would flow north and south along the rivers, with trade stations

springing up along the route. One of these was Novgorod, the site of modern day

St Petersburg. The local population called the newcomers the 'Rus' - who would

eventually give their name to the region as Russia.

In the middle of this web of trade routes sat the newly established trade centres

in the Scandinavian home lands such as the Danish town of Hedeby and Birka in Sweden. It

was here that the raw materials from the Scandinavia crossed the manufactured goods

from Europe and the luxury items from the East. These towns were originally started as seasonal

markets, but they quickly attracted a population of craftsmen, drawn by access to

materials and plentiful customers. Amber, furs, walrus ivory and iron mixed with

wine, glass, and ceramics in exchange for silver, spices and silk - and from all regions,

slaves.

Straight barter is sure to have taken place, but it was silver that was the common

medium of exchange for all. Jewelry might be used either whole or cut into fragments,

into what is called 'hack silver'. Coins from all regions were of a similar size,

and would be judged for purity based on an understanding of the honesty of each

maker as known though their marks. It is by tracing these silver coins back to

their original point of origin that modern archaeologist have learned much about

the extent of trade and have determined many dates. In all cases, the most valuable

tool for any trader was small a folding pan scale. All silver would be assessed

for relative value, then weighed out to finalize the deal.

Two cultural traditions of the Viking Age, trade - and violence, would put their

mark on the farthest flung voyage of all. In distant Vinland, the First Contact

between the exploring Norse and the resident Aboriginals would start off as a

matter of trade. The Sagas tell us that the Skraelings were eager to trade furs

for both milk and red cloth. As might be expected, the sharp dealing Norse started

reducing their side of the bargains as the supplies ran low. Despite this dishonesty,

it would be the Norse who started the violence, when a forbidden iron axe became

the item of desire. Thus ended the first meeting between the two long separated

branches of the human race.

It is hard not to wonder what might have happened if that first meeting had

not ended in open hostilities.

return to DARC main index

Dark Ages Re-Creation Company

Dark Ages Re-Creation Company